This month marks the 40th anniversary of an unprecedented clash on the silver screen, not between Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader, but rather, surprisingly, between James Bond and… James Bond.

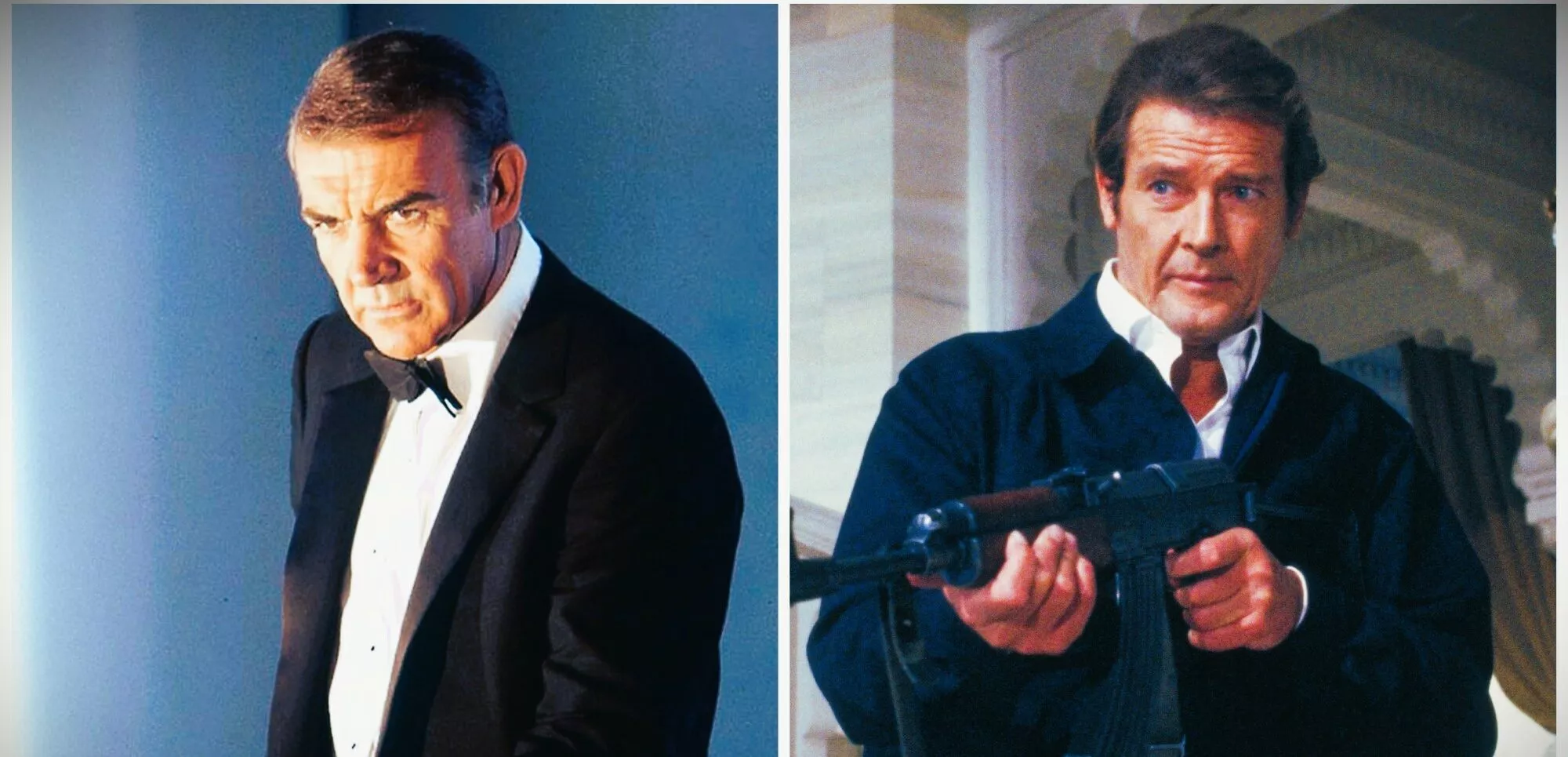

Back in 1983, moviegoers were presented with a unique choice between two films featuring Ian Fleming’s renowned secret agent. On one hand, there was “Octopussy,” the sixth installment showcasing the charismatic Roger Moore as the sophisticated British spy, Agent 007. On the other hand, “Never Say Never Again” emerged, marking the return of the original James Bond, Sean Connery, after a 12-year hiatus from the immensely successful film franchise. Connery had previously bid farewell to the role in 1971.

How did such a situation arise? Why did two competing studios decide to pit their films against each other, featuring the same iconic character? And more importantly, how was this legally permissible? The answer lies in a complex sequence of events that trace back to the 1950s, to the very inception of James Bond, and continue beyond 1983, stretching into the 2000s, right up until the onset of Daniel Craig’s tenure as Bond. At the heart of this story is a determined producer who single-handedly sought to create his own series of 007 movies – even if it meant repeatedly producing the same story.

The Name’s McClory, Kevin McClory

By 1958, Ian Fleming, the successful British author, had already written six out of what would eventually become a series of twelve novels featuring James Bond, the British Secret Service agent with a license to kill. Bond was known for his affinity for strong martinis, attractive women, and a troubled soul burdened by the violence and isolation of his profession.

It seemed inevitable that Bond would make his way onto the silver screen, although Fleming was surprised that the offers hadn’t come as quickly as he had anticipated. However, in 1958, everything changed when Fleming’s friend Ivar Bryce introduced him to Kevin McClory, an Irish film director and producer.

McClory had read Fleming’s Bond books and was captivated by the character. However, he didn’t believe the existing novels would translate well into films. Instead, McClory proposed creating an original story centered around Bond. Fleming, Bryce, Ernest Cuneo, and McClory brainstormed numerous outlines and treatments, exploring various titles such as “James Bond of the Secret Service” and notably, “SPECTRE.”

Fleming even made an attempt at writing a screenplay himself, but McClory was dissatisfied and enlisted screenwriter Jack Whittingham to refine the script. Accounts suggest that all parties involved contributed elements to the story: McClory proposed setting the film in the Bahamas and involving nuclear threats, Cuneo suggested underwater battles, while Fleming, McClory, and Cuneo all claimed to have contributed to the creation of the criminal organization SPECTRE and its villainous leader, Ernst Stavro Blofeld.

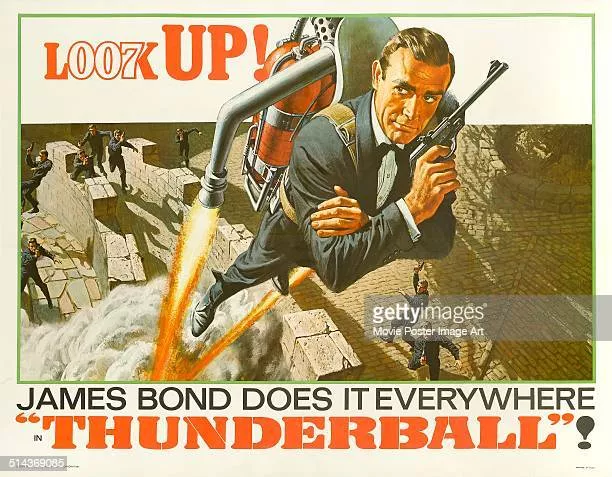

The end result was a script penned by Whittingham, initially titled “Longitude 78 West,” which Fleming later renamed “Thunderball.” While Fleming seemed content with the screenplay, he began doubting McClory’s ability to handle the potentially large-scale production. Their strained relationship, coupled with Fleming’s pursuit of alternative options, led to the collapse of the film project.

Meanwhile, Fleming had already started working on his ninth Bond novel, also titled “Thunderball.” Surprisingly, he incorporated elements from the unproduced screenplay without crediting McClory or Whittingham. McClory filed a lawsuit against Fleming in London’s High Court to halt the publication of the book. The case was eventually settled, with ailing Fleming (who had suffered a heart attack during the trial) granting McClory the film rights to the book, which had to be credited as “by Ian Fleming, based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham, and Ian Fleming.”

Little did anyone know at the time, McClory’s legal victory would have significant repercussions for the Bond franchise in the years to come.

Thunderballers

Following the publication of the book Thunderball, Ian Fleming embarked on negotiations that ultimately granted the film rights to almost all the James Bond novels, with the exception of the first one, Casino Royale, which had already been optioned by producers Albert “Cubby” Broccoli Jr. and Harry Saltzman. From that point on, Broccoli, and later Broccoli himself, and subsequently his heirs after his passing in 1996, have maintained control over the Bond film franchise, starting with Dr. No in 1962 and continuing to the present day. However, when they selected Thunderball as the fourth film in the series after the success of the first three movies, the producers encountered a significant hurdle.

That obstacle was Kevin McClory, who still held the film rights to Thunderball due to his legal actions against Fleming. Initially, Broccoli and Saltzman had intended to make Thunderball their first Bond film in 1961 and even commissioned a screenplay for it. However, the legal complications surrounding the book prevented them from proceeding at the time.

Determined not to lose control of the adaptation again, they struck a deal that involved McClory producing the film under their Eon Productions, while Broccoli and Saltzman served as executive producers. According to the book “Some Kind of Hero” by Matthew Field and Ajay Chowdhury, Broccoli expressed their concern, stating, “We had the feeling that if anyone else came in and made their own Bond film, it would have been bad for our series.”

In fact, that was precisely McClory’s intention. Annoyed by the success of the Eon series, McClory had already begun planning his own 007 movie and had even approached Richard Burton about playing the lead role. However, all his independent plans came to a halt when he agreed to the deal with Eon. Thunderball, released in 1965, became a massive hit and marked the pinnacle of the Connery era. The film is still regarded as a classic in the Bond franchise.

However, there was one lingering issue: McClory still retained the film rights to Thunderball. As part of his agreement with Broccoli and Saltzman, he was prohibited from producing another version of the film for ten years following the release of the original. Clearly, even Bond’s own producers hadn’t anticipated that they would still be making movies about the world’s most famous spy a decade later.

Exit Bond’s Greatest Villain

True to form, McClory made a public announcement in 1975 expressing his intention to independently produce a new James Bond film, once again based on the content of Thunderball. At the time, the Eon series, although having gone through various lead actors including Sean Connery (You Only Live Twice), George Lazenby (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service), and Connery again (Diamonds Are Forever), had now settled on Roger Moore as the iconic 007. Moore’s initial two Bond films, Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun, achieved moderate success, while the production of his third installment, The Spy Who Loved Me, was already underway when the prospect of a rival McClory film emerged.

Upon learning that Ernst Blofeld and the criminal organization SPECTRE, last seen in Diamonds Are Forever, would be featured as the primary adversaries in The Spy Who Loved Me, McClory filed a lawsuit against Eon, arguing that these elements could not be used as he, Whittingham, and Fleming had developed them. Ultimately, the court awarded McClory the rights to Blofeld and SPECTRE, forcing Eon to exclude them from The Spy Who Loved Me and all subsequent Bond films for many years to come.

However, both Eon and the Fleming estate accused McClory of overstepping his boundaries by utilizing Bond-related material that he was not authorized to use. As a result of ongoing legal battles waged against him by both parties, McClory’s project was abandoned (at least temporarily), and he was restricted to adapting only the material from Thunderball for any future attempts at creating a new 007 movie.

A ‘Mickey Mouse’ Production

Despite not having produced a film since Thunderball in 1965, McClory remained determined to fulfill his dream of making a James Bond movie. However, the looming threat of legal action from both Eon and the Fleming estate deterred other studios from getting involved. Eventually, in 1980, McClory transferred the rights to producer Jack Schwartzman, who skillfully navigated the legal challenges and paved the way for the film to move forward—with Sean Connery officially returning to reprise the role of Bond.

How did Connery become enticed to come back after previously swearing off the character following Diamonds Are Forever in 1971? The process began in 1975 when McClory approached Connery about writing the film (alongside screenwriter Len Deighton) and even potentially directing it. Although that particular version of the film didn’t materialize, Connery enjoyed the writing experience and started contemplating playing the part again.

When Schwartzman offered him a reported $5 million and a share of the film’s box office profits in 1981, Connery couldn’t resist. Feeling he had been underpaid for his efforts in the first five official Bond films, Connery saw this as an opportunity to both make up for past grievances and take a jab at Broccoli. “I’d own a significant portion of it, and the financial return would be in proportion to my investment, which hasn’t been the case before,” he said at the time, as documented in Some Kind of Hero.

With Connery on board, director Irvin Kershner (known for The Empire Strikes Back) chosen to helm the film, and McClory assuming the role of executive producer, Schwartzman enlisted writer Lorenzo Semple Jr., known for his work on the Batman TV series, to craft a screenplay that strictly adhered to the original Thunderball story to avoid further legal complications. However, Connery was dissatisfied with Semple’s purportedly campy tone and brought in his own team of writers to revise the script, with changes being made throughout the production (allegedly, Connery’s wife contributed the title, inspired by his previous declaration of “never again” to Bond in 1971).

Schwartzman encountered budgetary issues, which necessitated further trimming of the script and several action sequences. With the production funds running dry, Schwartzman reportedly used his personal finances to complete the film. Tensions escalated between him and Connery, with the latter essentially acting as a producer on set while Schwartzman kept his distance. Connery later referred to the production as “a chaotic operation.”

Simultaneously, Eon was hard at work on Octopussy, the 13th film in the official Bond franchise and the sixth to feature Roger Moore as 007. Although Moore had expressed a desire to leave the series after his previous film, For Your Eyes Only, Eon recognized the existence of Never Say Never Again and deemed it wiser to retain the established Moore rather than introduce a new Bond to compete against Connery’s return.

Director John Glen, who had successfully directed the more grounded For Your Eyes Only, returned to steer Octopussy in a similar direction. The film drew inspiration from a Fleming short story for its title and incorporated a few story elements, but otherwise presented an original narrative.

Unlike the turbulent production of Never Say Never Again, Octopussy proceeded smoothly under the well-established Eon machinery. However, in the background, long-time Bond franchise distributor United Artists faced financial difficulties and was eventually acquired by MGM. It was against this backdrop that Octopussy clashed with Sean Connery and Never Say Never Again in the summer of 1983.

Bond vs. Bond

Octopussy hit theaters first in June 1983 under the MGM/UA banner, generating significant promotional buzz proclaiming Roger Moore as the true James Bond. Posters and ads proudly declared, “Roger Moore IS James Bond.” On the other hand, Never Say Never Again, distributed by Warner Bros., was released in October of the same year (December in the UK), despite last-minute legal attempts by both Eon and the Fleming estate to halt its release. However, even Sean Connery acknowledged that it was better for both films to have a gap between their releases, stating, “It would have been stupid to bring them out at the same time.”

According to current Rotten Tomatoes ratings, critics had mixed reactions to both films, but Never Say Never Again slightly outperformed Octopussy with a fresh rating of 71 percent. Conversely, Octopussy received a rotten consensus with a 42 percent rating. Those who enjoyed Octopussy appreciated its continuation of the more grounded tone established in For Your Eyes Only, although some critics felt that the formula with Moore had become stale. As for Never Say Never Again, critics praised Connery and other cast members but criticized the idea of remaking Thunderball as pointless.

How do these films hold up today? Like many movies from the 1980s, they haven’t aged particularly well, although they still have their own appeal. Octopussy benefits from presenting more of a geopolitical thriller rather than a sci-fi adventure like Moonraker, but its attempts at humor often fall flat. Moore delivers his usual amiable and comfortable performance, and while Maud Adams is adequate in the title role, the remaining cast is largely forgettable.

The plot suffers similarly, with its convoluted mix of rogue Russian generals, exiled Afghan mercenaries, jewel smugglers, flirtations with nuclear blackmail, and an all-female circus troupe. It becomes nearly incomprehensible, and its villains are considered among the weakest in the Bond series. The movie heavily relies on Moore’s charisma and the action sequences, and while some fans appreciate it, many agree that Octopussy is one of the weaker entries of the Moore era. However, it does possess something that Never Say Never Again lacks: style, panache, and production value, despite having a budget $9 million lower at $27 million compared to its competitor’s $36 million.

Directed by a TV producer who struggled to complete the film, Never Say Never Again often oscillates between resembling a TV movie and a low-budget production akin to Cannon films. The action is confined in scale, and the pacing is sluggish—a flaw that also plagued the bloated Thunderball, although to a lesser extent. The plot mostly rehashes that of the 1965 original, with SPECTRE agent Maximillian Largo blackmailing the world using two captured atomic bombs.

Never Say Never Again lacks the familiar Bond trademarks like the pre-credits sequence, gun barrel opening, and the iconic Bond theme. The score is jazzy but feels out of place. M, Moneypenny, and Q make appearances, but with different actors and interpretations. However, Never Say Never Again remains highly watchable due to the presence of Sean Connery.

Connery, unabashed about his age (he was 52 during filming, ironically three years younger than Moore and looking better than his last two Bond films), effortlessly slides back into the role, exuding the same confident swagger and underlying intensity that made him a star the first time around. The film leans into the notion of Bond aging, with M threatening to retire him from the 00 division. Connery carries the film with a playful irony that benefits both him and the overall picture.

The remaining main cast members are also quite strong, with German actor Klaus Maria Brandauer delivering an offbeat and eccentric yet menacing portrayal of Largo, while Bernie Casey, the first actor of color to play the role, portrays a more rugged Felix Leiter. The women in the film, Barbara Carrera as the dangerously seductive Fatima Blush and Kim Basinger in one of her early roles as Domino, Largo’s lover and ultimately Bond’s ally, add beauty, sensuality, and intrigue.

In the end, Octopussy holds a slight edge over Never Say Never Again, despite Connery’s involvement in the latter, simply because it is better crafted. Audiences seemed to agree, as Octopussy outperformed Never Say Never Again, earning $187 million compared to the latter’s respectable $160 million worldwide. Neither film was a financial failure, indicating that audiences had an appetite for both Bond offerings.

However, Connery retired from the role for good this time, and Moore hung up his tuxedo after one more adventure in 1985’s A View to a Kill. Nonetheless, Eon Productions, led by Broccoli, persevered, while McClory also persisted. In the mid-1990s, as Eon revitalized the Bond series with Pierce Brosnan’s debut in GoldenEye, McClory announced yet another Thunderball remake titled Warhead 2000, with Timothy Dalton, Brosnan’s predecessor in the official series, touted as the lead.

The story of how this unfolded and ultimately led to Eon reclaiming not only the rights to Thunderball but also the outlier novel Casino Royale, however, is a tale for another time. As we all know:

James Bond will return.