David Johansen, the frontman for the New York Dolls, was the subject of the Showtime documentary “Personality Crisis: One Night Only,” co-directed by Martin Scorsese and David Tedeschi. The documentary premiered at The New York Film Festival, the same venue where Scorsese’s “Mean Streets” debuted in 1973, coincidentally the same year the New York Dolls released their first album.

During the Q&A session following the screening, Scorsese revealed that he used to play the Dolls’ music for the actors before shooting scenes in “Mean Streets.” He particularly highlighted the song “Personality Crisis” for its rhythm and blues roots, energy, humor, and the memorable back-and-forth between the singer and the band.

Johansen himself had a personal connection to the film. He recounted a chance encounter with guitarist and pianist Sylvain Sylvain, where they stumbled upon “Mean Streets” playing in a small cinema on Fifth Avenue and 13th St. They initially thought it was a documentary and Johansen may have even smoked a joint before realizing it was a fictional film. He described the movie as “beautiful” and mentioned that they had been in each other’s lives ever since that moment.

The documentary “Personality Crisis: One Night Only” inadvertently draws parallels between two iconic New York City artists, Martin Scorsese and David Johansen. Scorsese was a punk filmmaker who captured the essence of a fringe community with his independent film “Mean Streets,” while Johansen’s band, the New York Dolls, became the most visible underground band of their time. Now, Scorsese is entrenched in the film industry establishment and Johansen is an urban musical institution. However, the documentary’s true standout is Johansen’s alter ego, Buster Poindexter, a performer without ego but with “the best pompadour in the business.”

The documentary captures Johansen’s 70th birthday concert on January 9, 2020, at the glamorous jazz restaurant Café Carlyle at the Rosewood Hotel. The performance was attended by Johansen’s friends, including Debbie Harry, Ari Aster, and Penny Arcade. Café Carlyle, once home to American royalty like Jacqueline Kennedy, has become Johansen’s regular haunt, and his annual residency was cut short by the COVID-19 pandemic.

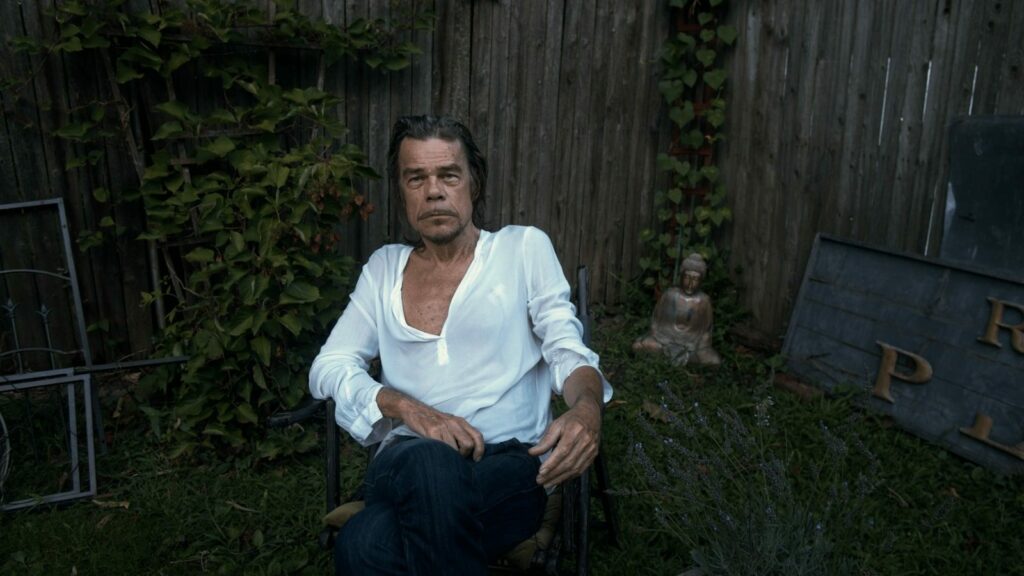

Johansen’s appearance is striking with his pencil-thin beard, John Waters-style mustache, black suit, and sunglasses. He looks more like a character from Scorsese’s “After Hours” than a performer at the glitzy Café Carlyle. During the documentary, he reveals that he created the Buster Poindexter persona as an act that could only play in New York. At the Café Carlyle, he admits to being in no mood for learning 20 new songs, so he replaces himself with his alter ego. The documentary is a concert film with archival footage and current interviews, showcasing the musical prowess of Johansen and the sophisticated elegance of Buster Poindexter.

During his second residency, Johansen curates a performance as his alter-ego, Buster Poindexter, who blends swing, blues, and rock to subvert the public perception of his former band, The New York Dolls. Johansen introduces himself to the audience as Buster Poindexter and invites them to join in on the playful act. This playful attitude towards music is reflected in Johansen’s comment, “They don’t call it working music, they call it playing music,” which sets the tone for the evening.

The concert’s ambiance is captured by strategically placed cameras that highlight the opulence of the Café Carlyle, providing an artful setting for Johansen’s performance. Johansen’s natural charisma and storytelling abilities, coupled with the Boys in the Band Band’s performances, create an inviting atmosphere that is expertly captured by cinematographer Ellen Kuras.

Johansen’s effortless banter with the audience and his band reflects an intimate connection, almost as if the viewer is present at the concert. The crew behind the camera also appears to enjoy the show, as evidenced by the deep affection displayed in the documentary.

The lineup for the show is fantastic, featuring tracks like “Lonely Planet Boy,” “Frenchette,” “Frankenstein,” and “Totalitarian State,” along with a lively rendition of “Funky but Chic” to open the set. The most noteworthy aspect is that every song is allowed to play out in its entirety, whether it’s performed live on stage or from archival footage. The editing team expertly uses match cuts to condense entire histories, sometimes incorporating various live performances, while still giving each song its proper conclusion. The only exception is “Hot Hot Hot,” which receives incomplete treatment from both the band at the Café Carlyle and past footage. In an interview, Johansen expresses his disdain for the overplayed track, which had become a ubiquitous annoyance for him. The omission of a full rendition is a stroke of brilliance.

Johansen’s path to joining The New York Dolls was an unconventional one, starting with playing school dances and participating in Staten Island battle-of-the-bands contests where he consistently placed second. He was a true revolutionary in a revolutionary era, but it came naturally to him. In an interview, he expresses his desire to break down barriers and just have a good time, regardless of sexual orientation, dietary choices, or any other labels.

The New York Dolls only put out two studio albums, both of which are essential listens, but their live performances changed the course of music. At the time, audiences were genuinely frightened by the band’s raw and raucous sound, which packed a harder punch than even the most badass rock gods. Their stage presence, which Morrissey describes as resembling “male prostitutes,” only added to their allure. In one of the archival clips, Poindexter affectionately refers to a former teenage New York Dolls fan club president as a “gloomy Gertie,” but acknowledges the deep love he had for the band.

Both Mean Streets and The New York Dolls emerged from tight-knit groups, from cramped apartment gatherings on the infamous “Hell’s Angels’ block” of 3rd Street, to Scorsese’s Little Italy neighborhood where he had to choose between a life of crime or priesthood. Scorsese took his Catholic guilt and used it as a weapon, bashing people over the head with a pool cue. Meanwhile, The New York Dolls took elements of social resistance, infused them with drug use and sexual defiance, and aimed to shake things up.

During a time when challenging gender identity could lead to physical harm, The New York Dolls fearlessly subverted norms. Johansen describes it as “the lie that tells the truth,” cutting straight to the point. Even though the band often had to resort to buying affordable women’s clothing from thrift stores to create their signature look, this boldness led to Johansen getting arrested in Memphis in 1972 for looking too much like Liza Minnelli. His mugshot could have been a rock album cover.

In the documentary, Johansen is asked about his feelings towards Kiss and Aerosmith for watering down The New York Dolls’ style and profiting off of it. With grace and class, Johansen points out that the more significant impact was on bands like The Ramones, who were inspired to pursue their own brand of punk music after seeing that if a guy like Johansen could do it, they could too.

In a flashback interview, Johansen recounts the moment that he believes The New York Dolls invented punk music. During a 1972 tour of England, the band was served an excessive amount of Newcastle ale as a welcome gift. Midway through their set, drummer Billy Murcia vomited gallons of beer without missing a beat, some of which splashed onto Johansen, who also proceeded to vomit mid-performance. The rest of the band followed suit, and the crowd erupted in applause. By the end of the tour, every band in England was puking on stage, but tragically, Murcia died from an accidental overdose during the tour. While the story may be humorous, the sad truth behind it is sobering.

Johansen’s stories are relatable, particularly to adventurous city kids, as he doesn’t spend much time reminiscing or putting much effort into it. Getting lost for weeks at the Chelsea Hotel was completely plausible. It is refreshing to hear Johansen’s lighthearted memories of dozing off while working the sound at the Ridiculous Theatrical Company and being invited to the avant-garde performances and political happenings that shaped the late 1960s. Johansen had the freedom to take advantage of the artists presented at the Mercer Arts Center before it crumbled under the weight of so much creativity, the sexually ambiguous flamboyancy of the regulars at Max’s Kansas City, the snarky putdowns of the Andy Warhol crowd, and the free political street art of Fluxus.

Johansen fondly remembers his mother telling him, “You’re a Communist dupe,” with a serious chuckle, “Maybe I was.” The way it is told makes it sound like so much fun, while the footage demonstrates how accessible it was. At any moment, Johansen could get a surprise knock from a Viking with a guitar but no singer, or a neighbor from down the hall who happened to be part of Up Against the Wall Motherfucker, the Dadaist, anarchist, Lower East Side direct action committee infamous for its beyond-hippie activist stance.

One of the most unexpected adventures revealed in the film is an impromptu political action. In February 1968, Johansen took part in one of the political theater group’s most inventive and noteworthy events. During the NYC garbage strike, Up Against the Wall Motherfucker gathered all the trash from the Lower East Side, dramatically transported it uptown via the subway, and dumped it at Lincoln Center on its gala opening night.

In the documentary, Johansen reminisces with ease about the industrial-sized tub of laundromat detergent that was dumped into a fountain, resulting in beautiful foam all over the fancy evening wear of the bourgeois cultural event attendees. These casual controversies contributed to his hepcat stage persona. On the other hand, Johansen’s equally captivating stories include passing an acting audition with Milos Forman for the film adaptation of Hair, being transformed into a graceful dancer by Twyla Tharp, but being told by composer Galt MacDermot that he couldn’t sing. Though told in a joking manner, it reveals much about the hardworking performer, whose father sang light opera while fixing their home’s roof on Staten Island.

Scorsese and Tedeschi, who previously co-directed The Fifty-Year Argument, have collaborated on several music documentaries, including George Harrison: Living in the Material World and No Direction Home: Bob Dylan. Schoonmaker edits Scorsese’s feature films, while Tedeschi has a knack for capturing character over narrative rhythm. Personality Crisis: One Night Only is stylistically akin to Public Speaking, the full-length documentary profile of Fran Lebowitz, with a focus on Johansen’s maturity, forever cynical and never jaded, during his Cafe Carlyle performance, allowing Scorsese to capture a slice of live with his microscopic attention to detail.