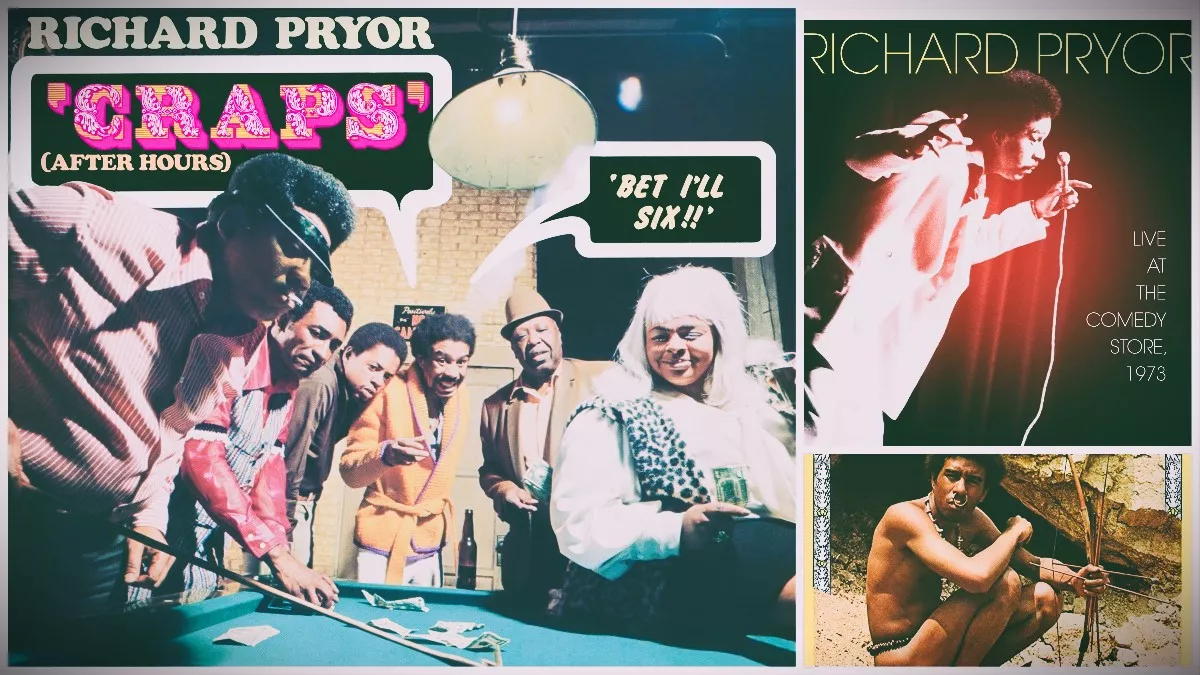

Richard Pryor’s impact on comedy went far beyond just reinventing the genre. He was a cultural trailblazer, not only in America but also around the world. As a five-time Grammy Award-winner, actor, writer, director, and standup icon, Pryor embarked on a personal journey of self-discovery that he fearlessly shared with audiences. His transformative years, spanning from 1968 to 1973, can now be explored through newly remastered vinyl reissues of his early live albums released by STAND UP! RECORDS, Omnivore Records, and Pryor’s production company, Indigo. The albums include Richard Pryor (1968), ‘Craps’ (After Hours) (1971), and the debut vinyl release of Live At The Comedy Store, 1973, along with bonus material that showcases the artist’s evolution into a revolutionary force.

Even without the visual element, the recordings demonstrate that Richard Pryor is a one-man theater troupe. His ability to embody and portray each character is so vivid that we can easily visualize them. He portrays these characters with love, even when using satire to dismantle them, as he uncovers their inner motivations, fears, false bravado, and confusion in ways that resonate with everyone and elicit sympathy. This approach doesn’t diminish the anger or soften the social commentary; instead, it sharpens the criticisms by exposing each character’s most intimate feelings. Pryor fearlessly pushed the boundaries of comedy, delving into these deeply personal stories to paint a broader picture of race, sex, and social unease from a universally relatable and authentically challenging perspective that also happens to be incredibly funny.

The Road to the First Album

Pryor’s journey into comedy took a serious turn during his time in the Army. After his dishonorable discharge, he dedicated himself to the craft and performed at various venues, including the “black and tan” Harold’s Club in Peoria and smaller clubs in East St. Louis, Youngstown, and Pittsburgh. He also found opportunities in burlesque houses and the “chitlin circuit,” where trailblazing comedians like Redd Foxx and Moms Mabley were breaking the color barrier at larger venues. Pryor expanded his horizons by performing at Borscht Belt clubs in the Catskills before eventually finding a niche in Greenwich Village coffee houses. There, he embraced social commentary and satire, inspired by influential figures like George Kirby, Dick Gregory, and Godfrey Cambridge, who were equally respected by contemporary groundbreakers like Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce. Pryor was particularly captivated by Bruce’s ability to challenge audiences, and the tragic overdose death of the latter in August 1966 fueled Pryor’s quest for defiant self-expression.

Similar to George Carlin, who later underwent a similar transformation under the label owned by Flip Wilson (whose impact on the art of comedy cannot be overstated), Pryor spent much of the 1960s crafting inoffensive material to appeal to a wider audience. He gradually gained recognition and made regular appearances on popular TV shows such as The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, The Mike Douglas Show, The Merv Griffin Show, and The Ed Sullivan Show. In his autobiography, “Pryor Convictions, And Other Life Sentences,” published in 1995, Pryor recounted a conversation with Groucho Marx at a party, where Marx posed thought-provoking questions about the kind of career Pryor desired and whether he aimed to be proud of his artistic path. This encounter served as an “epiphany” for Pryor and occurred in September 1967.

Pryor ventured into the Las Vegas scene in 1966 when Bobby Darin enlisted him as the opening act for his show at the Flamingo. While the details surrounding his on-stage “meltdown” at the Aladdin a year later are difficult to discern between fact and fiction, Pryor became increasingly aware that white audiences struggled to connect with the characters he was developing in his mind. He also felt constrained and repressed in order to cater to the expectations of the Strip. One night at the Aladdin, while under the influence of cocaine, Pryor caught sight of Dean Martin in the audience. In his autobiography, Pryor recalls feeling repulsed by the image he imagined he presented and desperately sought clarity, as if it were oxygen. In a burst of inspiration, he addressed the sold-out crowd, exclaiming, “What the fuck am I doing here?” before abruptly leaving the stage, albeit from the wrong direction.

Many believed this incident would hinder Pryor’s ability to perform at larger venues again. However, according to Scott Saul’s biography, “Becoming Richard Pryor,” Pryor eventually returned to fulfill his contract at the Aladdin, faced consequences for his profanity, and went on to do subsequent shows at Caesars Palace.

Richard Pryor’s Journey to Becoming the Namesake of His Iconic Album

Following the Aladdin incident, Pryor pursued less controversial opportunities and appeared on popular television shows such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Tonight Show, and The Pat Boone Show. He also had a guest appearance on an episode of The Wild Wild West and made his debut on the big screen in the 1967 William Castle film The Busy Body, which starred television skit comedy pioneer Sid Caesar. Notably, jazz legend Miles Davis, in a remarkable display of support, swapped Pryor’s opening act slot for a prime placement at an early 1968 show at New York’s Village Gate. This act served as an intuitive and generous vote of confidence in Pryor’s talent, as highlighted in Pryor Convictions. Additionally, Pryor secured representation from the agency that also handled the Beatles and the Supremes.

During this period, Pryor regularly performed at Redd Foxx’s club in Central Los Angeles, entertaining predominantly Black audiences and immersing himself in the teachings of Malcolm X, a close friend of Foxx. In Pryor Convictions, Pryor reflects on the importance of his breakdown, explaining how it allowed him to shed his artificial image and build genuine self-respect. He delved into Malcolm X’s collected speeches, actively seeking truth and gaining valuable insights into humanity and what it means to be human.

In 1968, while Pryor stood at a critical juncture in his career, teetering on the edge, the iconic album Richard Pryor was recorded live at the Troubadour in West Hollywood. It captured a pivotal moment in Pryor’s journey, as he navigated the uncertain path ahead.

The film Uncle Tom’s Fairy Tales, which was recorded in 1968, has never been officially released. Richard Pryor damaged the original prints of the film, but they were later reconstructed by Spheeris. Persistent rumors circulated for years suggesting that fellow comedian Bill Cosby acquired the film to prevent its release. When asked about the possibility of a print being stored in Cosby’s garage, Spheeris informed us that she and Jennifer Lee Pryor have meticulously searched through every piece of footage they could find. Unfortunately, Jennifer experienced a falling out with Bill Cosby and his wife Camille, and they refused to cooperate when she requested access to retrieve that footage.

When Pryor first arrived in New York City, he recognized that white America desired their Black comedians to conform to a colorless mold. After reading a Newsweek profile on Cosby and receiving advice from an agent that Cosby was better suited for mainstream white television, Pryor began imitating the popular comedian. In interviews, he even humorously referred to himself as “Richard Cosby.” Pryor admitted to The New York Times that he earned a significant amount of money by adopting the persona of Bill Cosby, but in doing so, he felt compelled to hide his true personality.

An Original Voice

Richard Pryor’s debut album marked a significant departure from the influence of Bill Cosby, establishing Pryor as a comedic force with a style entirely his own. In the liner notes of the album, Scott Saul remarks, “Richard Pryor alerted the world that Pryor had stepped out of Bill Cosby’s long shadow and developed a style—surreal, nervy, improvisational—that was all his own.”

Even when imitating others, Pryor possessed a unique essence. He engaged in surreal comedy, such as impersonating the first person to walk on the sun. Simultaneously, he honed his skills as a one-man theater performer, absorbing the personalities around him, finding humor in their idiosyncrasies, and fully immersing himself in character. While Cosby might deliver a comedic bit about giving his mother a piece of wood for her birthday or his father half a pack of the wrong brand of cigarettes, presented from the perspective of an adult, Pryor took a different approach. In the Richard Pryor track “Rumpelstiltskin,” when he becomes a kid, he fully embodies the childlike nature, allowing every aspect of his being to reflect that of a child. Even through audio alone, one can imagine the expression in his eyes and the animated way he moves.

Pryor brought a sense of authenticity to every character he portrayed on stage, from the manicured army lieutenant running “kill class” for recruits to a Black superhero with X-Ray vision that allows him to “see through everything but whitey.”

The album’s cover, designed by Gary Burden, garnered a Grammy nomination for Best Album Cover. Within the grooves of the record, Pryor revolutionized American comedy with an unprecedented style. The double-deluxe vinyl of Richard Pryor includes bonus material from the same period, originally released on Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966-1974). Some of these additional tracks capture Pryor engaging in improvisation, although his approach differs from the traditional improvised troupe suggestions. Pryor engages in open conversations and establishes deep connections with the audience, often simply because he enjoys the sound of someone’s voice.

Pryor finds profound personifications within language, allowing the sounds of words to shape characters and emphasizing emotions through breath. He consistently demonstrates sensitivity to pitch, inflection, and the natural rhythms of speech. Additionally, Pryor imparts lessons on natural history and draws unconventional conclusions. For example, on the track “Black Power,” he declares, “Black people didn’t have a god because we worshiped things like air, water, trees, each other,” highlighting how this was perceived as savage by white society. Yet, Pryor assures a racially provocative heckler during the show that there is no need to fear the Black man except for his thoughts, dispelling any concerns.

Richard Pryor’s debut album showcased his unmatched artistry, establishing him as a groundbreaking comedian whose voice and style resonated with audiences in an unprecedented manner.

Taking Risks and Finding Success

Comedy performances have often paralleled rock shows, reminiscent of the days when bootleg recordings of live acts circulated as “party records.” These recordings captured the raw and uncensored material of artists like Pryor, Foxx, Rickles, Hackett, and even the fictional but marvelous Mrs. Maisel. In 1966, Laff Records was established, specializing in raunchy and entertaining content. Their roster initially featured local Black comedians recorded at the York Club in South Central L.A.

On December 9, 1970, amidst personal turmoil, Pryor signed with Laff Records. He was grappling with the loss of his stepmother and father, his mother’s battle with cancer, a pending divorce filed by his wife Shelley, and separate lawsuits for child support from two other women. He was ensnared in a cocaine addiction and indebted to his dealer.

“By the end of 1970, I just felt full. I knew it was time to go back and resume my career as Richard Pryor, comedian,” Pryor reflects in Pryor Convictions. “For the first time in my life, I had a sense of Richard Pryor the comedian. I knew what I stood for. I knew what I had to do. I had to go back and tell the truth.”

Originally released in March 1971, ‘Craps’ (After Hours) was recorded at Maverick’s Flat and the Redd Foxx Club. Encouraged by Foxx and his frequent co-writer Paul Mooney, Pryor was granted the freedom to express himself without limitations. The album features 32 tracks that exude a casual and unrestrained atmosphere. Pryor’s tone is more aggressive, his attacks are direct, and his confessions are intimate and relentless. He fearlessly exposes his vulnerabilities, admitting to extreme paranoia and bouts of horrific jealousy. Listening to the album now, it becomes evident that Pryor is harsher on himself than on anyone else he targets with his jabs.

Except, perhaps, the nightsticks and billy clubs. Pryor doesn’t need to explicitly state that Black people in America live in a police state; he vividly portrays the experience of living in occupied territory. Yet, he maintains an open sense of humanity throughout. In “I Spy Cops,” he portrays a Black cop who feels compelled to outdo his white partner to secure his pension. In “The Line-Up,” he reveals police line-ups as a form of preparation for show business.

“This fascinating collection chronicles how Richard Pryor evolved from a nightclub comedian of the 1960s to becoming the voice of his generation,” writes Larry Karaszewski, co-writer of films like Dolemite Is My Name and The People vs. Larry Flynt, in the introduction to ‘Craps’ (After Hours). “The performances capture the moment when Richard Pryor stopped being polite, shed his suit, tie, and gloves, and began reflecting the realities of the streets and the counterculture.”

The album includes bonus material selected from Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966-1974) and No Pryor Restraint: Life in Concert. Pryor recorded the alternate version of “Wino & Junkie” and “Whorehouse, Pt. I” at the People’s Festival held at Laney College in Oakland, where he fearlessly delves into autobiographical material with political relevance. As Pryor states in Pryor Convictions, “I lived in a neighborhood with a lot of whorehouses. Not many candy stores or banks. Just liquor stores and whorehouses.” The event also featured the agricultural agitprop experimental troupe Teatro Campesino and the soulful sounds of The Lumpen, the official band of the Black Panther Party.

Unintended Revelation

In February 1971, following the destructive Northridge earthquake in Beverly Hills, Richard Pryor arrived in Berkeley, located in California’s Bay Area. In his book Pryor Convictions, he describes how Marvin Gaye’s iconic album “What’s Going On” became the backdrop of his life during that time. As Marvin sang the lyrics, “What’s goin’ on?” Pryor’s response was a candid, “Fuck if I know.”

In Berkeley, far removed from the chaos of his personal life and the pressures of Hollywood, Pryor’s stay solidified his message. He discovered it in the local bars, nightclubs, and barber shops of the Bay Area, as well as through conversations with influential figures such as Angela Davis, Huey Newton (Black Panther Minister of Defense), and writers Ishmael Reed, Cecil Brown, and Claude Brown. It was clear to Pryor that it was time to take his message to the masses.

Pryor began making appearances on prime-time television, including a guest role on The Partridge Family and scriptwriting for Sanford and Son and Flip Wilson. In 1973, he won an Emmy for co-writing two television specials for Lily Tomlin. Pryor also recorded his first concert film, Live And Smokin’, in 1971. The following year, he portrayed the character Piano Man alongside Diana Ross’ powerful portrayal of the troubled Billie Holiday in Lady Sings the Blues. He continued to secure roles in films such as Hit, Wattstax, and Uptown Saturday Night. Additionally, in collaboration with Mel Brooks, Pryor co-wrote a screenplay for a western called “Black Bart,” which was later released as Blazing Saddles with Cleavon Little in the lead role instead of Pryor.

In April 1972, the Comedy Store opened its doors in West Hollywood, becoming an established institution. Pryor’s performances at the Comedy Store on October 29 and 30, 1973 were recorded and released as Live At the Comedy Store, 1973. Originally intended for testing new material for upcoming shows at The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and San Francisco’s Soul Train Club, these recordings ultimately became a Grammy-winning and chart-topping album in 1974.

Live At the Comedy Store, 1973 features additional material from Pryor’s other albums, including …And It’s Deep Too! The Complete Warner Bros. Recordings (1968-1992) and Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966-1974). Richard Pryor’s comedic prowess is on full display as he updates his material and delivers madness with precision. He even engages in a form of speaking in tongues to connect with the masses, humorously suggesting that Jesus Christ possessed such immense power that he “turned a rock to stone.” In his routine “Wino and Junkie,” Pryor transforms his “Street Corner Wino” into a concrete messiah for a second coming.

The reissues of Richard Pryor’s albums, including ‘Craps’ (After Hours) and Live At the Comedy Store, 1973, serve as reminders that some societal issues remain unresolved. Nevertheless, the ability to speak powerful truths through unfiltered humor never loses its relevance or impact.

Wow, great job! Richard Pryor was a really great comedian

I have never heard of him, but because of this article, I now want to get acquainted with his work

You are welcome!