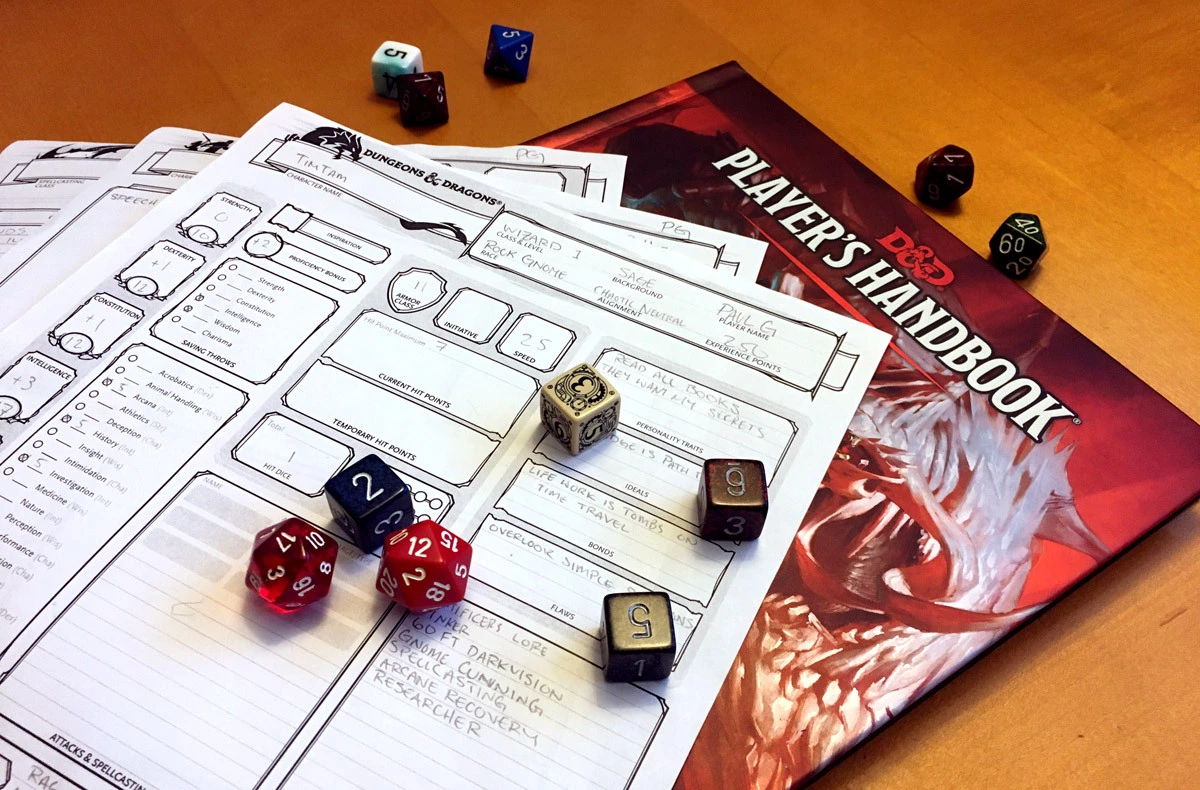

There’s an interesting scene in the first episode of the new season of Stranger Things. In it, the head of the Dungeons and Dragons school club reads an article whose author accuses the game of all mortal sins. It may seem that the creators of the series themselves came up with this moment, but in the 1980s, similar situations happened all the time.

Then, American society was very afraid of Satanists, and caring citizens struggled to look for them. Due to several fatal accidents, D&D fans were also viewed with suspicion by the general public.

We talk about the origins of the “satanic panic”, the most high-profile criminal cases initiated because of it, as well as the attitude of society towards Dungeons & Dragons fans.

Panic’s Origins

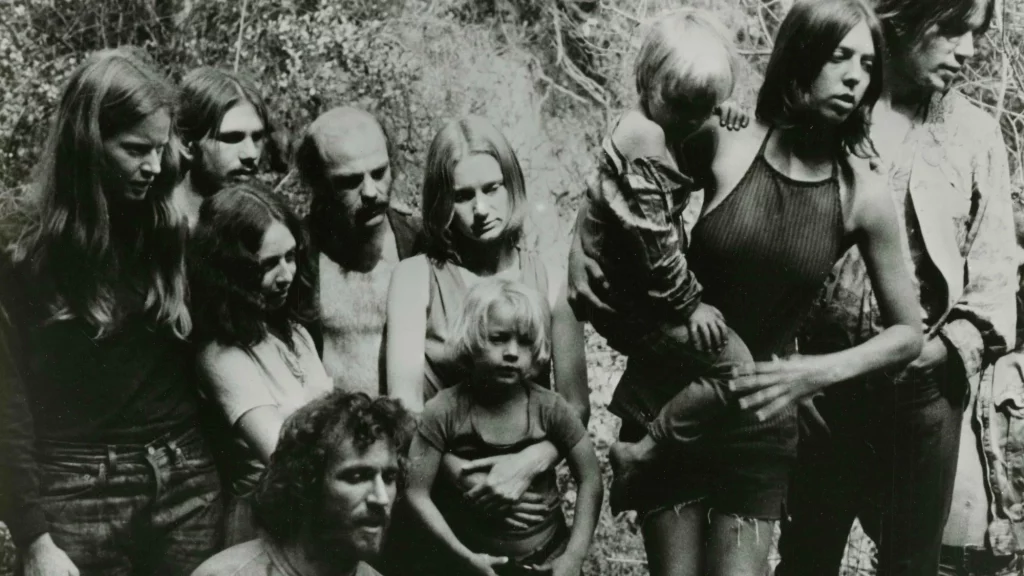

It all started back in the late 60s. It was then that a series of murders committed by members of the Charles Manson sect swept across the United States. These events reminded people that there are those among them who can commit terrible crimes for the sake of an abstract higher goal. In the case of Manson, it was the certainty of the future end of the world.

In the same period, society began to hear more and more about Satanism due to the fame of Anton LaVey. The showman founded his own Church of Satan and wrote an entire bible for it. At the peak of his popularity, he managed to attract thousands of people to his religion. Even now, he is called the founder of modern Satanism.

But LaVey’s daughter claimed that he did not really believe in his beliefs and was engaged in the church for the sake of self-affirmation and easy money. Be that as it may, LaVey undoubtedly contributed to what happened in the 80s.

In the mass consciousness, Satanism was associated with demons, dark rituals in groups of followers, and sacrifices. It is these symbols and the fears associated with them that have been exploited in culture, primarily by the authors of books.

So, in 1972, a work by Mike Warnke called “The Satan Seller” was released. It was an autobiography in which the author talked about his growing up in a sect dedicated to Satan. According to him, he was a priest and participated in every ritual imaginable, including orgies. However, the story of Warnke, according to him, ended well: over time, he turned to Christ and earned the forgiveness of those around him.

After 20 years, when the fear of sects began to decline, scientists have proven that the events of “The Satan Seller” are completely fictional. However, after the publication of the book, Warnke became a celebrity and even collaborated with the police on cases related to Satanism. Society willingly believed his stories: people believed that demon worship was becoming commonplace. And something had to be done about it.

Meanwhile, Hollywood began to make films on this topic (for example, “The Exorcist”), and members of different sects committed new crimes or mass suicides. In addition, in 1980, psychiatrist Lawrence Pazder published the book Michelle Remembers, which touched on another sore subject for society—child abuse.

The book was about the life of Michelle Smith, a patient of Pazder. According to the psychiatrist, he used hypnosis so that the girl could remember her childhood. During the sessions, the girl admitted that her mother was a member of a satanic cult, and Smith, at the age of five, experienced bullying and violence from other followers.

The book became a bestseller, and Pazder, like Mike Warnke, became a well-known expert on “satanic ritual abuse.” This term, by the way, was first used in Michelle Remembers.

As in the previous case, the events of the book were found to be unreliable a few years later. However, in the 80s, people who blamed abstract Satanists for all the problems were at the peak of popularity thanks to publications in the media, and their books were considered manuals for identifying supporters of sects.

As a result, people who had been reading about brutal murders and listening to stories about Satanists for years began to believe that even their neighbors could be members of cults. Therefore, they begin to look closely at others and sound the alarm for any reason.

Mass hysteria led to thousands of criminal cases, and that time began to be called the period of “satanic panic”.

Notable incidents

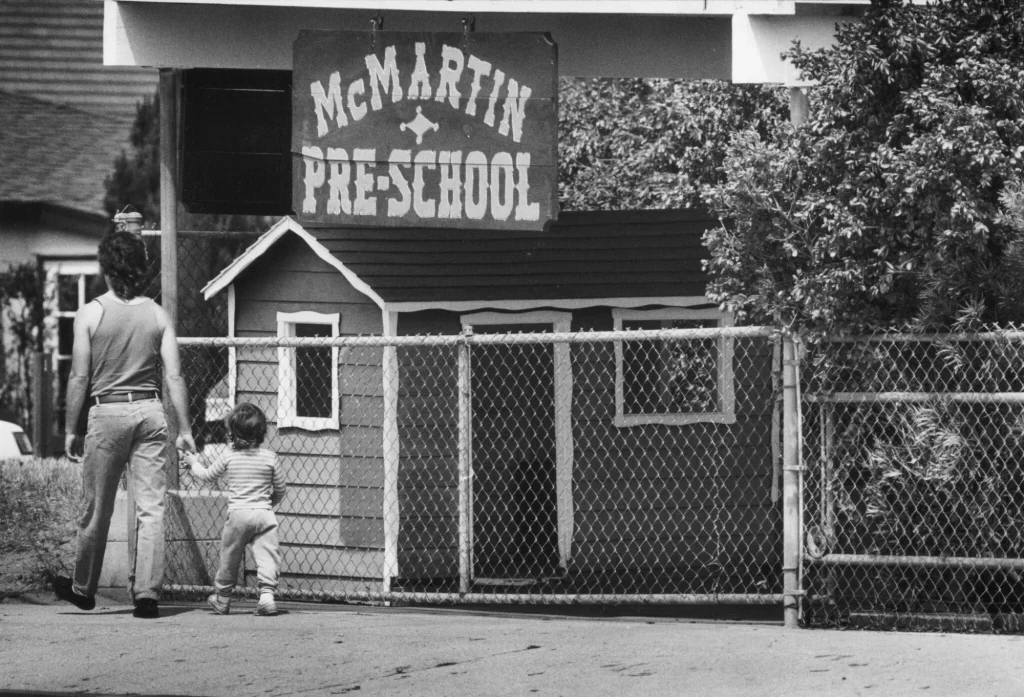

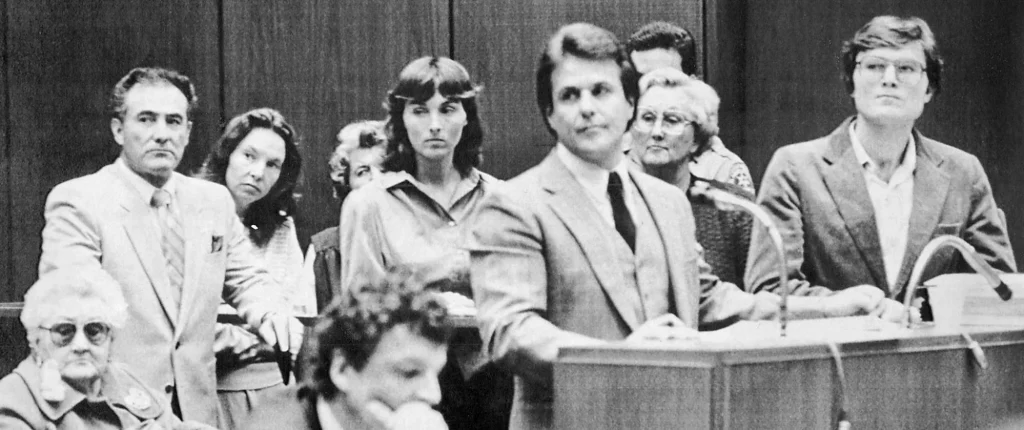

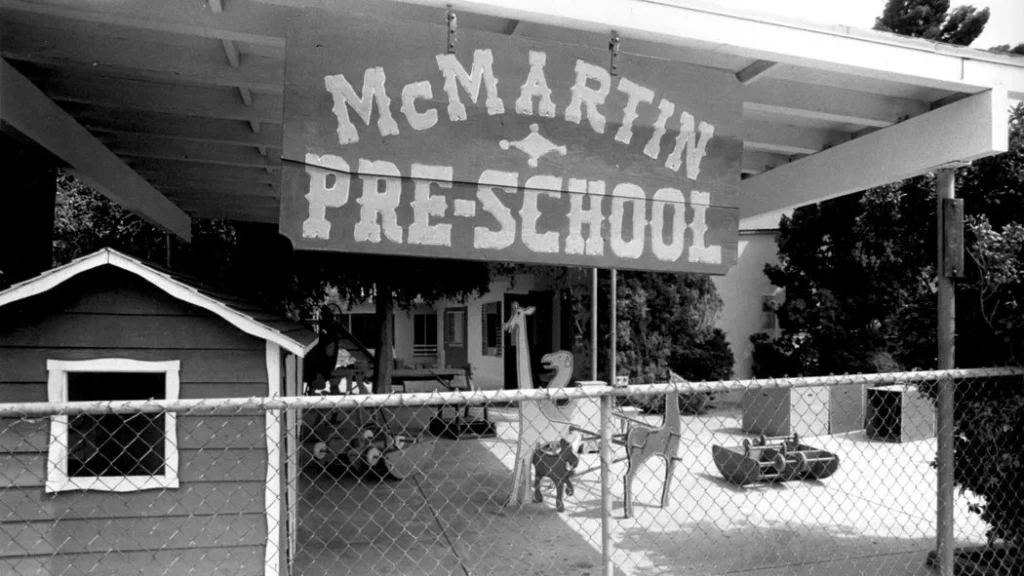

The loudest case happened in 1983 in the state of California. The mother of a McMartin family kindergarten student accused her ex-husband, who worked at the institution, of harassing her three-year-old son. The police, trying to understand the case, turned to parents whose children attended the same kindergarten for help.

Police and psychotherapist Key MacFarlane interviewed 400 children and identified 321 cases of violence by seven kindergarten staff. According to them, more than 360 children suffered in total. Immediately, began a large-scale investigation based on the horrifying testimony of children.

According to them, the offenders built a network of tunnels under the kindergarten, sacrificed animals and children, and also flew and wielded witchcraft. And this is only a small part of their statements. However, the investigation had no evidence other than oral confessions; they could not even find traces of violence on the bodies of children.

The accusations sounded absurd, but the proceedings caused a real panic throughout the country and reached the court in early 1986. Seven defendants were in the dock, but five of them were acquitted a week later due to a lack of evidence.

Prosecutors dropped the charges in 1990 after spending about $15 million over seven years on the investigation and trial. This criminal process is still considered the longest and most expensive in US history.

The reason for closing the case was the same: it was impossible to establish the guilt of the remaining defendants without direct evidence. The case is now being compared to a witch hunt in the 17th century.

Over the years, the public began to question the methods of psychotherapist McFarlane. As it turned out, she did not have the required license, and her conversations were rather strange. So, the specialist gave the children “anatomically accurate dolls” and asked them to show where the offenders touched them.

McFarlane’s critics also found that during interrogations, she pressured the children and pushed them in every possible way to admit that they were bullied, even if it was not true. Some children gave false testimony in order to be left behind, while others developed false memories.

MacFarlane believed that there were organized groups of Satanists in the United States who raped children. Therefore, she apparently tried by any means to knock out the necessary testimony from the children. This explains the tales of terrible rituals. True, the psychotherapist did not provide evidence of the existence of such communities.

Now the investigation seems absurd, but in the 80s all of America discussed it, and similar cases appeared constantly in the wake of the general satanic panic. Then, about 200 people fell under investigation, dozens of whom were convicted by mistake. Not everyone is lucky enough to be released after a couple of years after the review of their case.

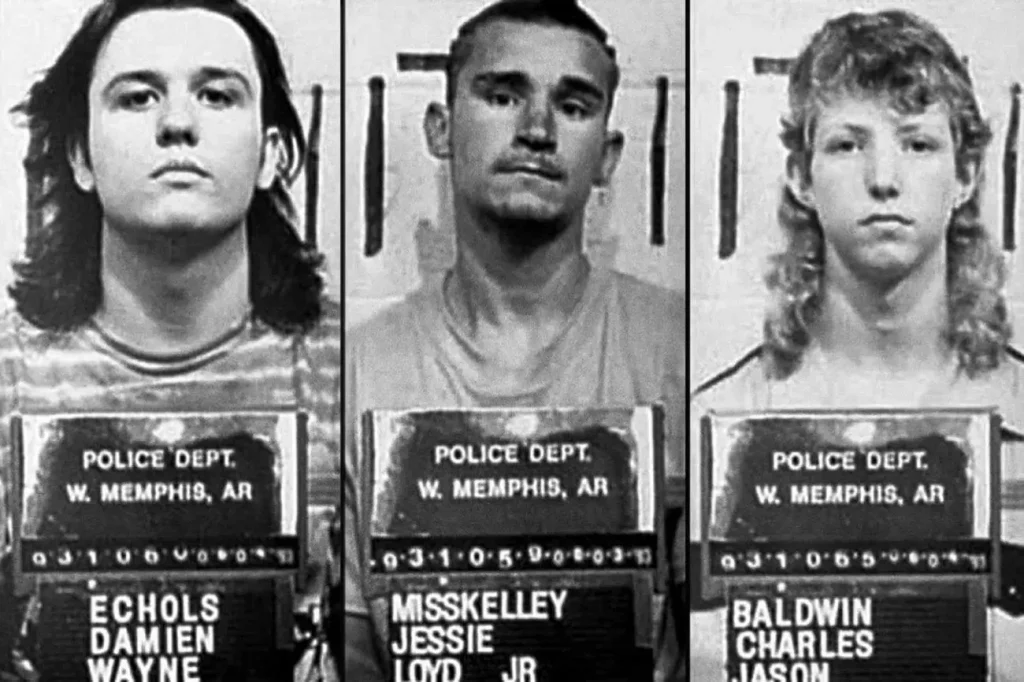

So, in 1994, three friends from West Memphis were sentenced to life imprisonment for the rape and brutal murder of three boys. But again, there were problems with the evidence.

Police were only able to extract a confession from one of the suspects after a 12-hour interrogation. But investigators still believed the teenagers were members of a satanic sect because they dressed in black, listened to heavy music, and were interested in the religion of Wicca.

The suspects were released only in 2011 because of new data: the defense managed to find out that there were no traces of their DNA at the crime scene. But they still had to make a deal with the investigation and plead guilty.

Yes, the trinity was released, but they, in fact, called themselves guilty. The judge counted them as having served 18 years in prison for punishment in the case. In the 1980s, courts handed down dozens of similar unfair sentences.

It was not only innocent people who suffered because of the satanic panic. For example, representatives of Procter & Gamble Corporation until 2007 went to court trying to prove that the company does not sponsor the Church of Satan, and its old logo is not related to the occult. Fans of Dungeons and Dragons have also received their portion of accusations.

Accusations against Dungeons and Dragons

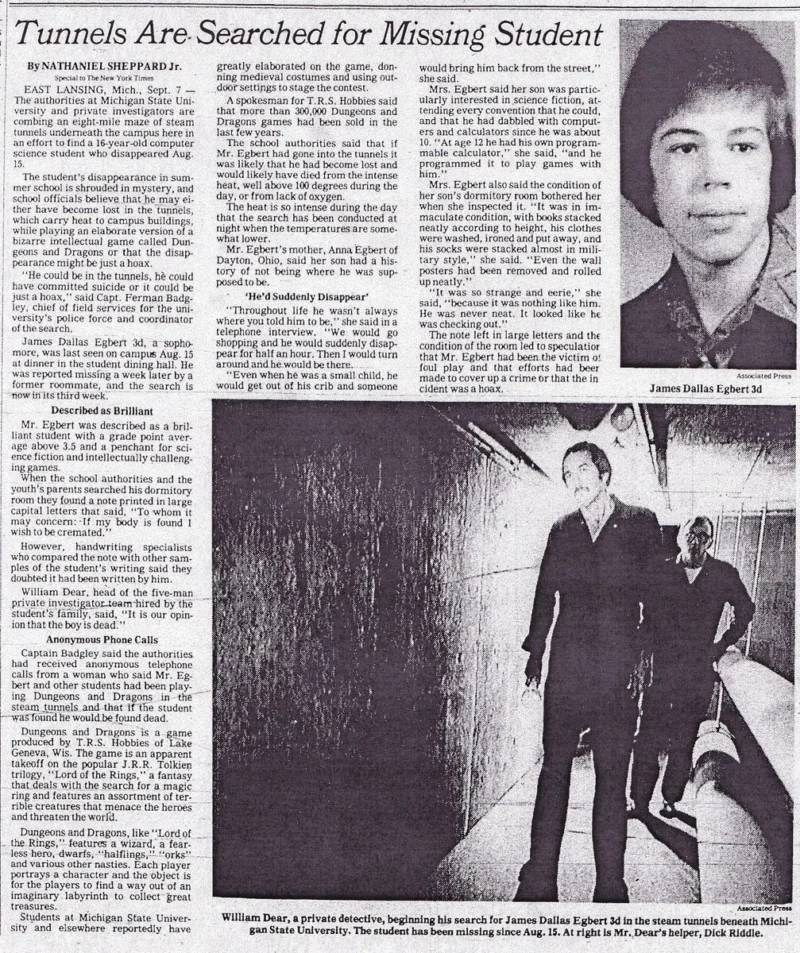

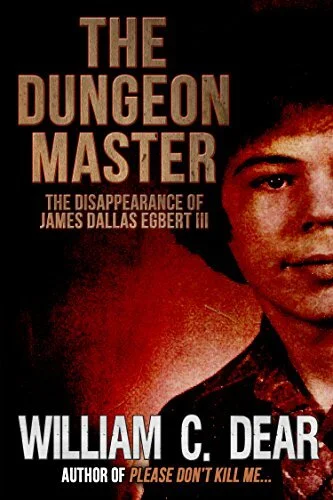

D&D was released in 1974, but it took five years for the game to truly become known in the US. In August 1979, all the American media wrote about the disappearance of a teenager, James Egbert, a student at the University of Michigan. According to the main version, the young man left the hostel, went down into the tunnels under the educational institution, and disappeared for several weeks.

Egbert’s parents hired a private detective who suggested that the boy’s psyche could be affected by his hobby, Dungeons and Dragons. The media echoed this version, and the entire country concluded that the popular game causes teenagers to lose touch with reality.There was even a version that something happened to the missing person right during the party that took place in those very tunnels.

But the reality turned out to be more prosaic. Egbert had a whole bunch of problems: depression, feelings of loneliness, drug addiction, and problems with his parents. He went down into the tunnels to commit suicide, but he failed. After that, he left the city and made a second suicide attempt.

A private detective found Egbert a few weeks later, but he did not return home, staying with his uncle. A year later, the young man shot himself. However, society remembered only that the boy was fond of Dungeons and Dragons.

According to his story, they wrote the book “Labyrinths and Monsters”, which quickly received a film adaptation with Tom Hanks. Writings about the dangers of role-playing games caused even more panic for parents, who already constantly hear about the ubiquitous Satanists. Not surprisingly, Dungeons and Dragons has become part of this narrative.

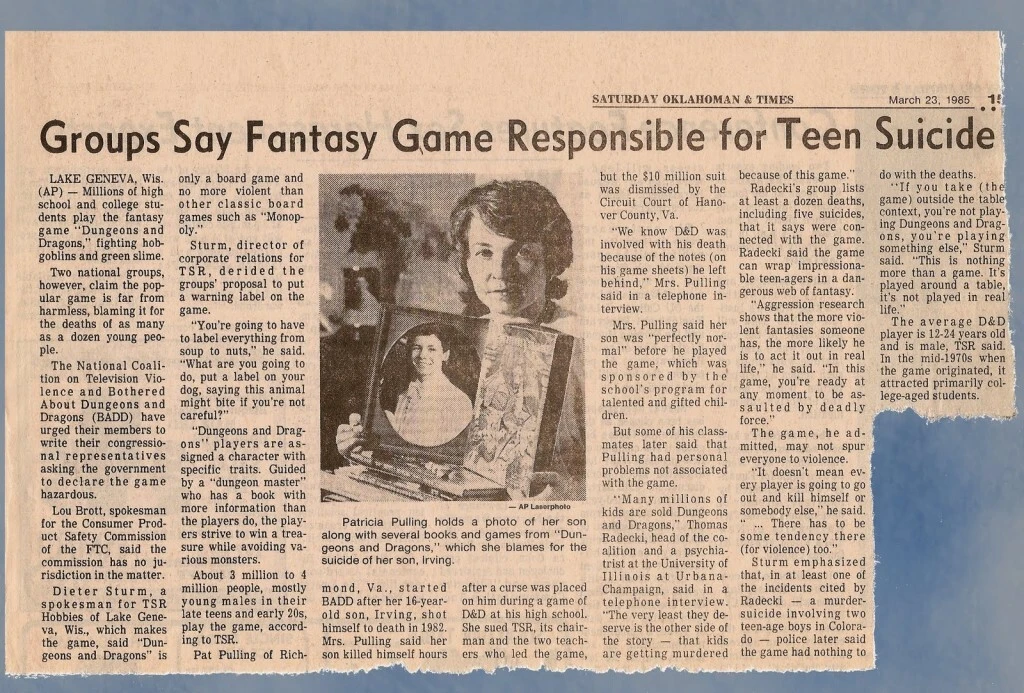

There have been other tragedies involving D&D fans. So, in 1982, the schoolboy Irving Lee Pulling, who became interested in the game shortly before the tragedy, shot himself. His mother immediately blamed everything on Dungeons and Dragons, sued the principal for allowing children to play in school, and founded the BADD (“Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons”) movement.

The woman claimed that the game promoted, among other things, satanic rituals, summoning demons, and necromancy, and that her son committed suicide after being cursed by another player.

The activist was unable to obtain compensation from the school and the authors of Dungeons and Dragons or to ban the sale of the game, but she made enough noise in the media. Meanwhile, Pulling’s class teacher and his classmates noted that the young man could not fit into the team and suffered from other problems not related to the game.

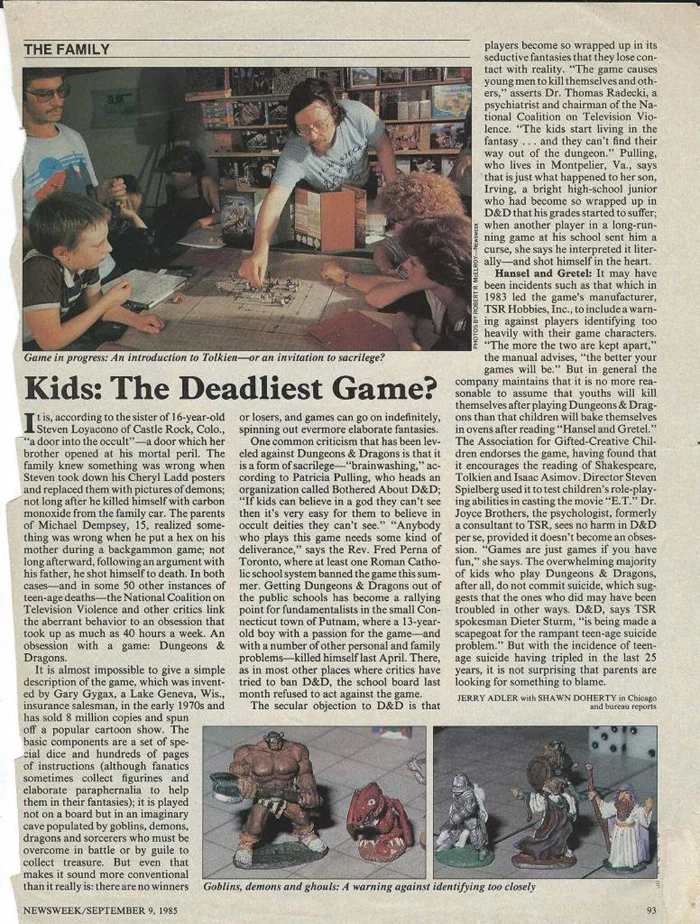

Against the backdrop of tragic incidents in the United States, a whole campaign was launched against D&D: the game was blamed for everything, not only in newspapers and on TV. Across the country, social and religious activists sued the organizers of school Dungeons and Dragons clubs, as well as burned books on the subject. Notable players were called sectarians without hesitation.

The argument that it was just a game was not taken seriously by the activists. They really believed that children could believe in the reality of demonic creatures. Moreover, some parents whose children committed suicide claimed that they summoned devilish beings before they died.

Activists believed that if demons were mentioned in Dungeons and Dragons and religious symbols were encountered, then the events of the game could be taken seriously.

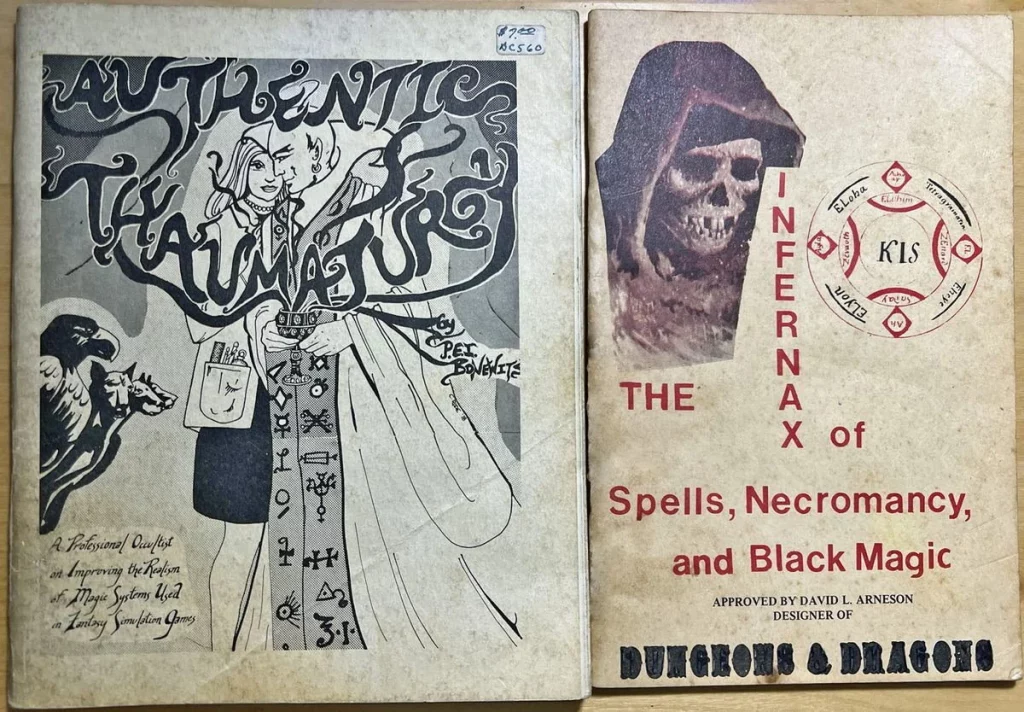

In addition, especially enthusiastic fans reworked the magic system in the game, adding their own spells, created according to the texts of medieval books. Many controversial symbols were usually added to the covers of such works.

The creators of D&D publicly defended their creation and called the persecution of players a “witch hunt”. They had statistics on their side: for example, the activists failed to prove that there were more suicides among the fans of the game than in other social groups. Scientists came to similar conclusions. In a word, the entire campaign against Dungeons and Dragons was based on exploiting the mood of people frightened by high-profile murders.

But by the mid-80s, the authors nevertheless took action. So, the book about D&D creatures was renamed from Deities & Demigods to Legends & Lore, and by the end of the decade, words like “demon” and “devil” disappeared from the game-they were replaced with made-up terms (for example, “baatezu”).

All these names returned to the game after 15-20 years, and this time they did not anger anyone. And in general, scandals only increased the popularity of D&D.

Of course, the satanic panic was spreading to other countries, and even in the 21st century, people were accused of “demonic rituals.” But these isolated cases can still not be compared with the mass hysteria of the 1980s.

As for Dungeons and Dragons, it is unlikely that anyone will begin to suspect the tabletop of promoting something forbidden. Millions of people around the world, including celebrities, are fond of it, and the game has been entrenched in pop culture for a long time.

For example, the main characters of the most popular Netflix show love Dungeons and Dragons, and knowledge of it helps the characters overcome difficulties. It is unlikely that the activists who called for a boycott of the game 40 years ago could have imagined this.